The Fantasy Gods Hate Me

Introduction

A running saying in my fantasy football league is ‘the fantasy gods must just hate me’. Although it’s used by some far more than others, everyone has said or thought it, at least once. Luck is an undeniably large part of the game when it comes to fantasy football. Sure there are rules that a league can implement to reduce it, but like most competitions we can never fully get rid of it.

Fantasy football is a game in which you, as a competitor, have no way of affecting your opponent. There are things you can try such as neutralizing some of their scoring by starting their quarterback’s recievers, or doubling down on a matchup by starting their best player’s opposing defense (PSA: these strategies are proven to be statistically insignificant). But ultimately it comes down to a weekly generation of numbers out of two independent data sets, with each player doing nothing more than praying that theirs is higher. So then why bother having matchups? Why isn’t the standard to have a Rotisserie league where you gain points for your performance relative to the entire league, not just one randomly assigned opponent? Or why don’t we just name the player at the end of the season with the most points the champion? The reason is simply that matchups are fun - they give us that “any given Sunday” vibe and tickle everyone’s inner gambler. What it also means is that the “best” team doesn’t always win - it brings luck into the picture.

Up until this season, I never put much thought into who the fantasy gods “hate”. I sort of just looked at who had the most or least points scored against them and deemed them to be the unluckiest and luckiest players in the league, respectively. But this season something else caught my eye. My team wasn’t the cream of the crop by any means (5th out of 12 most points) but it still had a win total that I didn’t think reflected my performance, at least compared to others. Our league consists of a thirteen week long regular season and this year we had 7 teams finish with 7 or more wins, 6 of which made the playoffs. My team finished with 6 wins, tied for 8th most in the league. Scoring the fifth most points and missing the playoffs by a game is not an unheard of tale, but I did notice as the year went on that I simply was never able to catch a break in terms of my opponents score. I went back and did a quick check to learn that throughout the entire season I had zero matchups where my opponent scored less than 80 points. Looking at the other participants in the league I noticed that everyone else had at least two such matchups and two teams had as many as six. This was enough to pique my interest and dig further.

So how can we determine how luck or unlucky someone is? The way I see it there are two different streams of luck that can affect a fantasy result: roster luck and opponent luck. Roster luck is the luck that surrounds player injuries, suspensions, trades, outlier seasons (good or bad), etc. If your first round pick tears their ACL week one that is certainly unlucky. However, quantifying the impact that has on your final result is quite the tall task. At least for right now, I am not focusing on roster luck. What this post will look at is what I call opponent luck.

As I said before, fantasy is a competition in which each side has no way of impacting their opponents score - you can’t play defense. If you score the second most points in a given week but go up against the person who scored the most, you’re eating an L. Sorry about it. And of course, on the contrary, you can score the second least amount of points but if you go up against the biggest loser of the week…you’re eating a W. This means your schedule can have a massive impact on your record, regardless of how many points you score. The goal of this project is to retroactively look at the season’s results and quantifiably determine who was the luckiest and who was the unluckiest.

Gathering Baseline Data

The first thing I wanted to do, after gathering all of the matchup results data from our fantasy website, was figure out every person’s mean and variance for their points scored and points against on the season. These numbers would help provide baseline inputs for further analysis.

For a quick lesson/refresher: the mean is the average score per week, or total divided by thirteen (weeks in a season). The standard deviation is the square root of the overall variance. Variance is a cumulative value used to measure how far spread out numbers are from their mean - in this case it gives us a look into scoring consistency. For a quick example, let’s consider the following two data sets:

Set One: [ 2, 2, 3, 3 ]

Set Two: [ 0, 5, 1, 4 ]

They will have the same mean of 2.5 but Set Two will have a larger variance (0.25) than Set One (4.25) since the individual numbers in Set Two have a larger cumulative distance from the mean.

The standard deviation, also a measure of spread, is used to calculate the probability a number will fall within a certain range of the mean. In a normal distribution we expect 68% of the numbers to fall within one standard deviation of the mean. So if we have a data set with a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3 we would expect 68% of the numbers in our data set to fall within the range of 7 to 13. If you want to learn more or just want to read a more concise explanation you can do that here.

For reference, across the entire league there was a weekly mean of 92.23 points scored and a standard deviation of 25.13. The results for each owner are shown in the table below. Please refer to the Appendix for visual plots of this data.

| Owner | Points For Total | Points For Mean | Points For Std Dev | Points Against Total | Points Against Mean | Points Against Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| charles | 1239 | 95.31 | 24.19 | 1319 | 101.46 | 14.09 |

| charlie | 1090 | 83.85 | 10.01 | 1095 | 84.23 | 27.79 |

| connor | 1288 | 99.08 | 25.35 | 1214 | 93.38 | 27.89 |

| fish | 1155 | 88.85 | 17.26 | 1269 | 97.62 | 27.42 |

| fratt | 1380 | 106.15 | 21.66 | 1178 | 90.62 | 26.71 |

| keefe | 1025 | 78.85 | 23.65 | 1194 | 91.85 | 17.73 |

| mark | 1226 | 94.31 | 26.08 | 1332 | 102.46 | 26.72 |

| nick | 909 | 69.92 | 17.12 | 1242 | 95.54 | 17.84 |

| pine | 1140 | 87.69 | 24.53 | 1020 | 78.46 | 16.89 |

| roger | 1186 | 91.23 | 20.0 | 1108 | 85.23 | 33.39 |

| scott | 1397 | 107.46 | 33.17 | 1179 | 90.69 | 23.5 |

| tyler | 1353 | 104.08 | 21.05 | 1238 | 95.23 | 22.8 |

This confirmed my initial thought that my team went up against an abnormally low variance of scoring - zero matchups with opponents scoring less than 80 points - which played a part in my team’s (lack of) success. It’s a good start but it doesn’t show us everything.

Relative Performance

I said it above and I’ll reiterate it here - I am trying to figure out who was the most unlucky in regards to their opponents performance. The mean and variance of points against paints a decent picture of magnitude and consistency, respectively. But I wanted to find a way to assign a numerical value that can help show the effects of schedule randomization. Because this is a competition where players can’t affect their opponent’s score, schedule randomization can make or break a season.

One of the first things I thought of, that was also relatively easy to compute, was how each perons’s opponents did against them relative to their yearly output. In other words, how many times did someone go up against their opponent’s best performance of the year? Second best performance? Worst performance? You get the picture. Let’s look at a basic example.

Let’s say I lose a matchup 81-87. Relative to the league average, both 81 and 87 aren’t strong scores. On the surface I may have no reason to be upset over scoring that amount of points and losing. But what we can’t see by just looking at this one matchup is that my opponent may average 70 points a week with a standard deviation of 15. If that happened to be the case than 81 points should be enough to win that matchup roughly 75% of the time. So despite the fact that I may have put up a low number, I may still be considered unlucky if I go up against a weak opponent who has one of their best weeks of the year.

The following table shows the relative ranking of every team’s opponents relative to their own sets of scores. There are thirteen weeks in the regular season so if I went up against a person’s high score of the season one week then that would count as 1 and if I went up against their low score of the season it would count as 13, regardless of the actual score. For this calculation the lower numbers are considered less lucky than the higher numbers. This metric may also prove useful down the line because it is not dependent on scoring rules. In other words, this will hold weight whether you have standard scoring or PPR, one QB or two, etc.

| Owner | Opponent Average Relative Ranking |

|---|---|

| charles | 5.31 |

| charlie | 8.62 |

| connor | 6.85 |

| fish | 6.69 |

| fratt | 7.15 |

| keefe | 7.0 |

| mark | 4.92 |

| nick | 6.46 |

| pine | 8.92 |

| roger | 8.08 |

| scott | 7.23 |

| tyler | 6.23 |

According to this metric we can see that Mark was, on average, going up against each person’s 4th or 5th best performance of the season each week. On the other side of the coin is Pine Street (Marty and Blake), whose opponents were averaging close to their 9th best (or 4th worst) performance of the year against them.

Like in any competition, it’s important to rack up wins against the bad teams in order to minimize the impact of a loss against the stronger teams. It’s a lot harder to do that when bad teams are putting up decent numbers, relative to their own expectations. For Mark and myself there were no easy buckets. For Pine Street, Charlie, and Roger the goalie was pulled with 15 minutes to go in the third. #sports

Expected Win Counts

The final thing (for now) that I wanted to calculate was the expected number of wins for each team. At the end of the day winning is what we care about most and thus something that we should quantify if we want to determine who was lucky and who wasn’t.

Thankfully we already have all the data we need to calculate the expected number of wins for each team. In order to figured out the expected win count I leveraged the expected value equation for a discrete random variable. That sounds a lot fancier than it is. Basically what it means is that the expected number of wins in a given week can be expressed as the number of wins you receive if you score more than your opponent times the probability you score more than your opponent PLUS the number of wins you receive if you score less than your opponent times the proability you score less than your opponent. Bear with me here. We already know by the basic laws of competition that if I score more points than my opponent then I receive “one” win. Likewise if I score less than my opponent I receive “zero” wins. Now let’s say that the probability I score more than my opponent is being expressed by the variable p. That means that the probability I score less than my opponent is 1-p, assuming there are no ties. Now that we know all that we can put our expected wins into a simple equation that reads like this, where E[X] represents the expected number of wins in a given week:

E[X] = (1 * p) + (0 * (1-p))

E[X] = 1 * p

E[X] = p

Using this expected wins equation for a single week we can then say that the expected number of wins a team is expected to get in a full season is the sum of pᵢ for each week where pᵢ is the probability that the team in question will score more points than their opponent in week i.

Seems easy enough, but how to we calculate pᵢ? Great question, astute reader. Luckily since our data sets are normally distributed we can leverage the cumulative distribution function or CDF. When provided a value x the CDF will return the probability that a value in that distrubtion (with a given mean and standard deviation) is less than or equal to x. This is the secret sauce that will make this all come together. Hold onto it, we’ll be back.

For our scenario, we want to know the probability that a score from Player A’s distribution, referred to as X, will be more than a score from Player B’s distribution, referred to as Y. Using basic arithmetic we can deduce the following:

P(X > Y) = P(X - Y > 0) = 1 - P(X - Y <= 0)

From our understanding of cumulative distribution functions we know that P(X - Y <= 0) is equal to the CDF of 0 for the normal distribution of X - Y. So all we need to do is figure out the mean and variance of X - Y. Because X and Y are independent, we know that the mean of distribution X - Y is equal to the mean of X minus the mean of Y. We also know that the variance is equal to the variance of X plus the variance of Y.

This should finally give us everything we need. To quickly summarize, the expected number of wins in a given matchup is equal to the probability that a player scores more points than their opponent. We can figure out that probability by constructing a new distribution based off of both players means and variances. Once we figure out these new means and variances we can use the cumulative distribution function and some basic arithmetic to provide an expected number of wins for a given matchup. We will run through this process for each matchup on a player’s schedule and then add up all of those expected win numbers to see how many wins each player was expected to win on the season given their scoring numbers and their schedule.

Hopefully we’re all on the same page. If not, well then I suppose it doesn’t really matter and you’ll just have to trust me. Here are the results:

| Owner | Actual Win Count | Expected Wins | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| charles | 6 | 6.834 | -0.834 |

| charlie | 7 | 4.764 | 2.236 |

| connor | 8 | 7.789 | 0.211 |

| fish | 6 | 5.76 | 0.24 |

| fratt | 9 | 9.179 | -0.179 |

| keefe | 4 | 4.368 | -0.368 |

| mark | 5 | 6.886 | -1.886 |

| nick | 2 | 2.476 | -0.476 |

| pine | 9 | 6.041 | 2.959 |

| roger | 7 | 6.466 | 0.534 |

| scott | 8 | 8.803 | -0.803 |

| tyler | 7 | 8.634 | -1.634 |

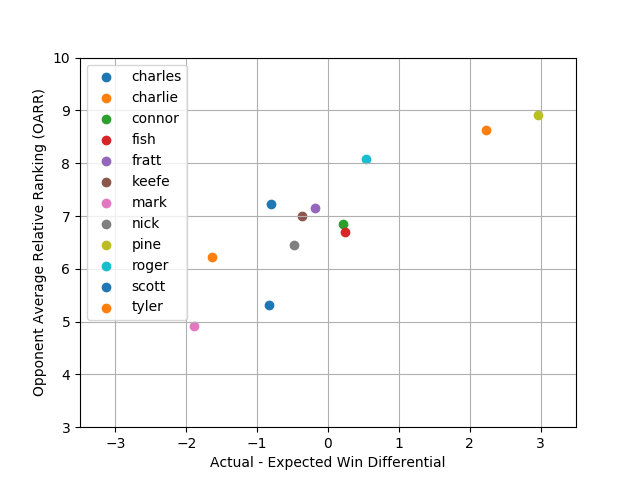

The expected number of wins tells us how many games each team was expected to win, given their scoring distribution and their opponent’s scoring distribution. So any team with a negative difference would be considered unlucky as they won fewer games than could be expected for a team with their schedule and scoring. Teams with a positive difference are the lucky ones as they won more games than could be expected of them. Based on our understanding of expected win differential, we can expect to see a negative correlation between the differences from this table and “Opponent Average Relative Ranking” (OARR) from above. Unsurprisingly, this shows us that the Pine Street People (with Charlie not too far behind) had a staggeringly lucky outcome while the likes of Mark and Tyler had a tough time catching any sort of breaks.

You can see a similar calculation to this one in the Appendix. That calculation varies by comparing each team with the league-wide scoring distribution instead of their opponent’s. So instead of calculating P(X - Y <= 0) for each matchup where X is a number from Player A’s distribution and Y is a number from Player B’s distribution, I calculated it where X is still Player A but Y is a number from the league-wide distribution (mean 92.23, standard deviation 95.13). You will also find a comparison between the schedule-relative expected wins and the league-relative expected wins.

I don’t find the comparison between those calculations to have an immensely large impact on determining who is the most “lucky” but I do find it fascinating in that it demonstrates the value of having bad teams in your division/on your schedule. For more on that check out the Appendix.

But what does it all mean, Basil?

At this point I think you’ve heard me battle through enough bouts of verbal diarrhea and I’ve thrown enough numbers your way that we can logically form opinions on the answer to our initial question. Just how lucky (or unlucky) was everyone this year? Let’s start from the beginning and review piece by piece until we reach a verdict.

In general, I think it’s fair to say that when a scoring average is at either extreme, a low standard deviation reinforces that extreme. In other words - if my average points against is very high then a low standard deviation is less preferable than a high one. And if my points against is very low then a low standard deviation is more preferable. The main reason I find this to be true is that margin of victory is completely irrelevant. It doesn’t matter if I win or lose by 5 or 50. So a high average combined with a low standard deviation means I’m going to have less matchups where my opponents score a relatively low number of points. Taking that same average but applying a high standard deviation means there are going to be a few matchups where I get completely blown out but there should also be a couple stinkers in there that should be easy wins.

Knowing that, it’s fair to say that strictly looking at the distributions of points against you would probably say that Mark, myself, and Nick had the toughest battle to face. On the flip side it would be Pine Street, Charlie, and Roger who had the most luck on their side.

The next layer we looked at was the Opponent Average Relative Rank (OARR). To me this didn’t reveal a ton of new information. In a way it sort of baked the points against results down into one digestable number. It certainly reiterated that Mark and I had a rough go of it and it really highlighted Pine Street, Charlie, and Roger’s fluff schedules. A couple of things that I found interesting:

- While Mark’s opponents averaged just one more point a week than mine, his OARR was almost .5 lower. This is likely attributed to Mark’s higher variance. While I might have more consistently gone up against my opponent’s fifth or sixth best performance on the year, Mark was more likely to see their best or second best mixed in with some 7-8th best performances.

- Pine Street’s opponents averaged their fourth worst performance of the year against them, the most extreme result on either end of the spectrum…by a lot. It will be interesting to look at this result compared to years past to see where it stacks up all time.

Now for the main course. What better way to bring this study home than to tangibly quantify by how much each person outperformed or underperformed their statistical expectations? The results were pretty consistent with the previous findings plus a couple of surprises. Mark and Pine Street were at either end of the spectrum with Mark coming up almost a full two wins short of his expectations and Pine Street outkicking their coverage by close a full THREE wins. Coming up behind Pine Street is Charlie who outperformed expectations by over two wins. Nothing we haven’t seen already.

What did come as a surprise to me was Tyler having the second largest deficit between actual and expected wins with roughly -1.5. He only had the fifth most points against and a pretty middle of the pack variance. So why was he expected to win so much more than he actually did? After looking closer I noticed an interesting occurance with Tyler’s results. His margin of a victory, whether it be low or high, was pretty large every week. Basically when he had a strong week, he happened to go against a weaker opponent score, and when he had his subpar performances he was going against strong opponent scores.

That sounds pretty normal: when you don’t do well you’re more likely to lose and when you do well you’re more likely to win. But where Tyler became unlucky is that he didn’t have a single occurance where he his team was able to not do their best and still steal a win. He had zero victories where his team scored less than 100 points. For context, Pine Street had four such occurances, Charlie had six (out of his 7 possible), and Roger had four.

For next time it will be interesting to determine a way to quantify that scenario. It sounds like a “quality wins” metric is in order. For now it’s time to wrap this up. I think it’s become pretty clear that for this season Mark took the crown for most unlucky with myself and Tyler not too far behind. Purely based off of opponent performance I think I had worse luck than Tyler. But when you factor in that Tyler had a better team and thus had higher expectations the argument could be made that he had it worse. I’ll leave that up to you.

On the other side of the spectrum I can’t even say that this was anything other than a one horse race. Pine Street took the cake in a landslide. To put up below average scoring numbers and come out of the regular season tied for the league lead in victories is quite remarkable. I’m excited to see how this compares with years past. The only other person who was within reach was Charlie who also separated himself from the pack by somehow winning seven games while putting up the third fewest points in the league.

I believe the chart below does the best job at capturing everyone’s luck on a scale. On the x-axis is the win differential (relative to schedules) and on the y-axis is OARR. The top right represents the luckier folks while the bottom left represents the less fortunate of the bunch.

So there you have it. My first stab at quantifying luck. Going forward, I hope to continue doing this for all seasons in the future and in the past and will be sure to post them here if/when I do. If you have any questions, thoughts, corrections, comments, etc…I’d love to hear them so pass them along!

Appendix

League Context:

- Standard scoring - No decimals, small bonuses for long touchdowns and yardage totals

- Rosters - 1 QB, 2 RB, 2 WR, 1 TE, 1 RB/WR/TE, 1 K, 1 D/ST

- Three divisions, four teams per division

- Play division opponents twice, and seven of eight remaining teams once

- Divisions winners seeded 1-3 (first be record, then by points), followed by three wildcard teams

Figures:

| Owner | Points For | Points Against |

|---|---|---|

| Charles | Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

| Charlie | Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

| Connor | Figure 5 | Figure 6 |

| Fish | Figure 7 | Figure 8 |

| Fratt | Figure 9 | Figure 10 |

| Keefe | Figure 11 | Figure 12 |

| Mark | Figure 13 | Figure 14 |

| Nick | Figure 15 | Figure 16 |

| Pine | Figure 17 | Figure 18 |

| Roger | Figure 19 | Figure 20 |

| Scott | Figure 21 | Figure 22 |

| Tyler | Figure 23 | Figure 24 |

Expected Wins Relative To League-Wide Scoring Distribution:

A quick note regarding the findings - In our league we have three divisions with four teams in each division. Each person plays everyone in their division twice and seven of the other eight owners once in the regular season. There were six owners who shared a division with either Nick or Keefe (two lowest scorers on the year) and all six of them have an expected value of schedule wins greater than their expected number of wins relative to the league has a whole. Those six are Pine, Connor, Mark, Fratt, Tyler, and Roger. Similarly, there were four owners who went up against Keefe or Nick one time combined: myself, Fish, Keefe, and Nick. All four of us had less expected wins relative to our schedules than we had relative to the league averages. The only other person to have less expected schedule wins was Charlie who played the weakest links twice.

The following table represents expected wins relative to the league-wide scoring distribution.

| Owner | Actual Win Count | Expected Wins | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| charles | 6 | 6.97 | -0.97 |

| charlie | 7 | 4.862 | 2.138 |

| connor | 8 | 7.517 | 0.483 |

| fish | 6 | 5.907 | 0.093 |

| fratt | 9 | 8.674 | 0.326 |

| keefe | 4 | 4.484 | -0.484 |

| mark | 5 | 6.806 | -1.806 |

| nick | 2 | 2.916 | -0.916 |

| pine | 9 | 5.812 | 3.188 |

| roger | 7 | 6.334 | 0.666 |

| scott | 8 | 8.399 | -0.399 |

| tyler | 7 | 8.388 | -1.388 |

The following table shows the comparison of expected wins relative to each person’s schedule and the league average.

| Owner | Actual | Expected (Schedule) | Expected (League) |

|---|---|---|---|

| charles | 6 | 6.834 | 6.97 |

| charlie | 7 | 4.764 | 4.862 |

| connor | 8 | 7.789 | 7.517 |

| fish | 6 | 5.76 | 5.907 |

| fratt | 9 | 9.179 | 8.674 |

| keefe | 4 | 4.368 | 4.484 |

| mark | 5 | 6.886 | 6.806 |

| nick | 2 | 2.476 | 2.916 |

| pine | 9 | 6.041 | 5.812 |

| roger | 7 | 6.466 | 6.334 |

| scott | 8 | 8.803 | 8.399 |

| tyler | 7 | 8.634 | 8.388 |

“What if…“

Below you can find a comparison of the actual playoff results with what the playoff standings and results would have looked like based off of expected schedule-relative wins. Divisions were still taken into account - top three seeds are division winners, three wildcards. The results are based off of actual scores from weeks 14-16.

| Actual Standings | Expected Standings |

|---|---|

| 1. Fratt - BYE 2. Pine - BYE 3. Scott 4. Connor 5. Tyler 6. Roger |

1. Fratt - BYE 2. Scott - BYE 3. Connor 4. Tyler 5. Mark 6. Charles |

Actual Results:

Round 1

Roger(6) def. Scott(3)

Connor(4) def. Tyler(5)

Round 2

Roger(6) def. Pine(2)

Connnor(4) def. Fratt(1)

Championship

Connor(4) def. Roger(6)

Expected Results:

Round 1

Connor(3) def. Charles(6)

Tyler(4) def. Mark(5)

Round 2

Tyler(4) def. Fratt(1)

Connnor(3) def. Scott(2)

Championship

Tyler(4) def. Connor(3)